By all indications, urgent warnings against “Christian nationalism” (CN) will continue as a major media theme through Election Day 2024.

Journalists will need to be careful with a tricky label that’s mostly shunned by supposed participants in the CN movement and employed by opponents (as with “fundamentalist” or “ultra-“ or “cult”). How complex is the fighting about this term? Click here to tune in some of the YouTube debates.

Critics’ typical definition comes from attorney Amanda Tyler, who leads Christians Against Christian Nationalism (with a large “N”) and the proudly progressive Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. She says CN “seeks to merge American and Christian identities, distorting both the Christian faith and America’s constitutional democracy.” Its “mythological” view of founding of a “Christian nation” means America is singled out “to fulfill God’s purposes on earth.” Further, CN “demands a privileged place for Christianity in public life, buttressed by the active support of government at all levels.”

Writers could pursue this sort of theme sideways by reviewing or collecting pro and con reactions to “How to Be a Patriotic Christian: Love of Country as Love of Neighbor,” the latest book by middle-roading evangelical Richard Mouw of Calvin University, formerly president of Fuller Theological Seminary.

Otherwise, here's a rundown to guide journalists on some of the notable CN chatter since The Guy took a whack at the definition issue last year year at GetReligion.

Hang on, because this gets complex. For starters, ambiguity abounded in an October Pew Research survey.

Some 60% of adults think – yes – the founders intended the U.S. to be a “Christian nation,” and 45% think it actually “should be” such, though for many that means only generalized moral guidance while only 18% think the phrase indicates Christian-based governance. Importantly, a 54% majority had never even heard of CN.

That belief the U.S. “should be” a Christian nation was favored by fully 65% of Black Protestants (compared with e.g. only 47% of Catholics). Yet University of Texas political scientist Eric McDaniel wrote for TheConversation.com that CN believes the only “true” Americans are “white, Christian and U.S.-born and whose families have European roots.”

The bizarre displays of Christian piety by some at the January 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot — or if you prefer, attack or insurrection — gave elements of the CN movement new media attention, and this month’s second anniversary provoked a new round of discussion.

Anticipating this, Tyler testified at a hearing (.pdf here) led by U.S. House Democrats last month. Yet a major investigation of January 6 by her Baptist agency and the Freedom from Religion Foundation found scant factual evidence of participation there by recognized church or “Religious Right” leaders.

Religion News Service posted (with usual disclaimer) the remarks at a January 6 prayer vigil by Craig Claiborne of Red Letter Christians. He assailed CN as doctrinal “heresy,” a “confusing perversion of the gospel of Christ” that uses religious language and symbols “but betrays the heart of our faith.”

Meanwhile, an article on Washington University’s Religion & Politics site used the anniversary to advocate strict “separation of church and state” and indict pretty much the entirety of U.S. Protestantism for fusing religion and nationhood when, for instance, “mainline” clergy open U.S. House and Senate sessions with prayer or the American flag is displayed in local churches.

If your head is not spinning yet, The Guy turns to critics of CN alarmism represented by Hillsdale College historian D.G. Hart. His intriguing January 9 Acton Institute assessment focuses on tenets said to define CN in two scholarly attack books, “Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States,” timed before the 2020 election, and “The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy,” which responds to the Capitol attack.

The books’ key CN tenets are that the U.S. should be declared a “Christian nation”; the federal government should advocate “Christian values” and religious symbols in public spaces, and allow public-school prayers; criticism of “separation of church and state,” and belief that “the success of the United States is part of God’s plan.”

On that last point, Hart wonders “how could anyone who believes in a sovereign God not believe some divine purpose is responsible for America’s place in the world?” As with many polls, he finds this typical of a discussion that’s “either misleading or imprecise.”

The historian applied the books’ criteria to himself and found he counts as a “nationalist” though on the “low end.” Yes, Hart is conservative in both religion and politics, but what does nationalism signify when he’s the author of “A Secular Faith: Why Christianity Favors the Separation of Church and State”? Since some combination of faith and national identity “is part of the historical imagination of many Americans,” and always has been, he suggests we all calm down.

Newswriters will also want to consider another RNS anniversary piece by veteran Bob Smietana, which concluded a series funded by the Pulitzer Center. He proposes that CN be understood as a constellation of these six “loose networks of faith leaders and followers.”

* “God-and-country conservatives.” These largely unorganized folk, including your own friends and neighbors as reflected in the Pew survey, harbor nostalgia for a faithful nation that’s “more aspirational than historical.”

* “Religious right’s old guard,” of culture-war evangelicals such as Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council, Southern Baptist seminary President Albert Mohler or David Barton, an ardent debunker of “separation of church and state.”

* “MAGA/QAnon.” These assorted activists include those who believe Democrats “stole” the 2020 election from Donald Trump, combined with adherents of the QAnon and other conspiracy theories.

* “The extremely online.” These Internet-based nationalists have been thrown off more mainstream social-media platforms and run other outlets. A typical performer here is Trump’s dinner guest Nick Fuentes.

* “Trump prophets.” Christian media personalities like Eric Metaxas combined with “self-proclaimed prophets” and “prosperity Gospel” preachers who believe God ordained Trump to win in 2020. Some come from the New Apostolic Reformation while others in that Charismatic movement explicitly reject CN. (Julia Duin has been covering this flock for years here at GetReligion.)

* Patriots and theocrats.” This refers especially to primarily secular groups like the Proud Boys, so prominent on January 6, who have increasingly added religious expressions to their advocacy of “patriotism and hypermasculinity.”

Finally, The Guy advises journalists to beware the Hasty Generalization Fallacy. Be careful out there.

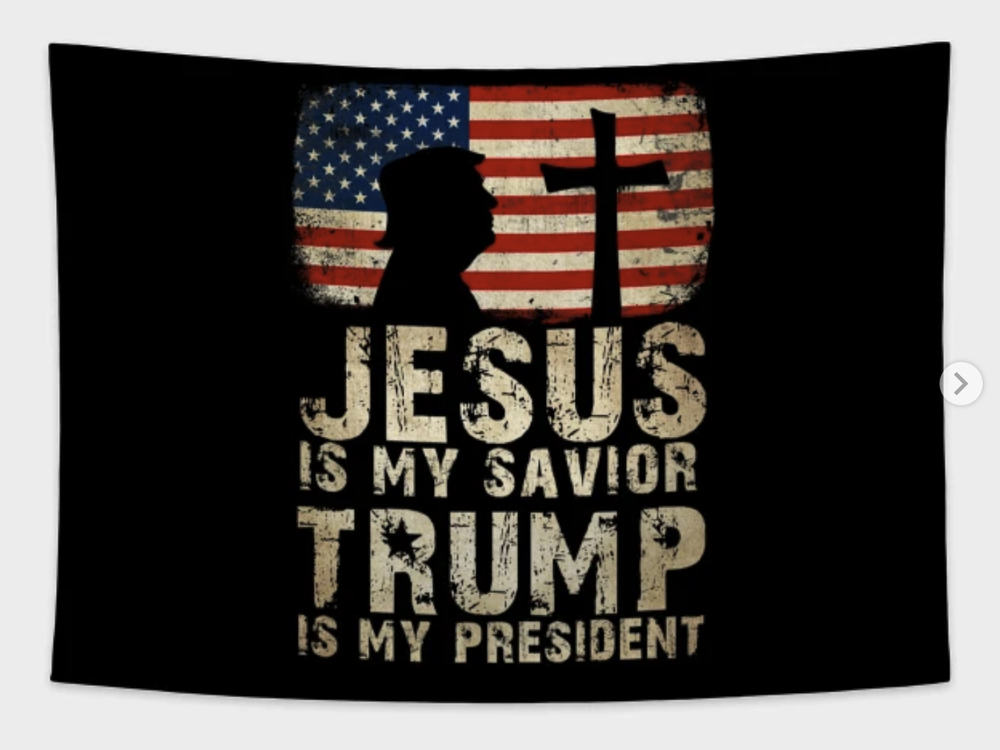

FIRST IMAGE: Tapestry for sale at TeePublic.com.