We can expect that the U.S. House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 Capitol attack will unveil findings in time to help Democrats' Nov. 8 prospects and, thus, spur Republican ire.

Even if the report ignores the matter, this report can peg thoughtful and thorough journalistic re-examination of the religious significance of continuing furor over the nine troublesome weeks from the 2020 vote through Jan. 6. Carefully balanced, non-partisan contexting will be needed.

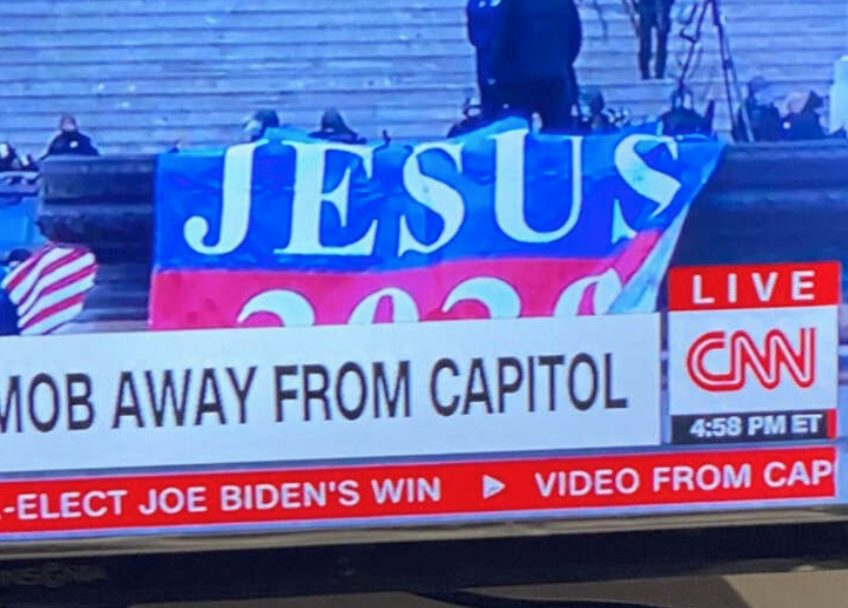

Media and amateur videos show us that – yes – some of the rioters uttered prayers and brandished Christian signs, slogans and symbols. Were they isolated cranks, or representative of a broader religious phenomenon, or a bit of both?

A New York Times anniversary walkup last week counted 275 defendants with federal charges for obstructing Congress, 225 or so for acts against police, and another 300 for minor trespass or disorderly conduct. So far, a fifth of these defendants have admitted legal guilt.

Importantly, the Times reported that the mob included "church leaders" (plural).

In a national newspaper, that phrase suggests not some small-time parsons from independent churches but notable media stars, denominational and "parachurch" officials, influential college and seminary thinkers, or at least local pastors from "big steeple" congregations. In fact, that reference appears to echo this Times passage that has been discussed several times here at GetReligion, referring to religious image on Jan. 6:

The blend of cultural references, and the people who brought them, made clear a phenomenon that has been brewing for years now: that the most extreme corners of support for Mr. Trump have become inextricable from some parts of white evangelical power in America.

At some point, it would be good to cite examples of “church leaders” linked to “evangelical power.”

By contrast, last year The Washington Post's Michelle Boorstein perceptively profiled certain of the rioters to highlight Americans' growing trend of concocting idiosyncratic "do it yourself" religions for themselves. "For many, their religious beliefs were not tied to any specific church or denomination – leaders of major denominations and megachurches, and even President Donald Trump’s faith advisers, were absent that day. For such people, their faith is individualistic, largely free of structures, rules or the approval of clergy," she wrote.

Veteran religious freelance Steve Rabey (a former GetReligion scribe) pursues this for the investigative Roys Report. He says though "numerous pastors" attended President Trump's "stop the steal" rally that fateful day he can identify only one, Tyler Ethridge, among the estimated 2,500 rioters who subsequently entered the Capitol.

Ethridge was not charged with a crime and, significantly, was fired as a youth pastor at Christ Centered Church in Tampa. A Christian historians' blog says Ethridge, a recent graduate of Charis Bible College, is a devotee of the Seven Mountains variant of radical Dominion theology, meaning he's hardly representative of conservative Christianity at large.

His Charismatic/Pentecostal movement does include a coterie of "prophetic" preachers who announced that God told them Trump would win. Some have apologized but many did not or clasp to a dream of Trump restoration. GetReligion's own Julia Duin explored this exotic terrain for Newsweek and she has been writing about this topic for years here at GetReligion.

Leaving aside crimes by the hundreds on that single day, is an insidious "Christian nationalist" movement gradually infiltrating the nation's churches and threatening its democracy? The politics editor for New York Times Opinion, Ezekiel Kweku, chose a proponent of such alarms, Katherine Stewart, for the religion analysis in a Jan. 6th package. Stewart is the author of "The Good News Club: The Christian Right's Stealth Assault on America's Children" (2012), followed by "The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism" (2020).

She told Times readers that "the most serious attempt to overthrow" constitutional government since the Civil War and "install an unelected president" would not have been feasible without "Christian nationalists." In her scenario, a sizable Christian population that backed Trump's "coup attempt" lives in an "information bubble" that consumes only sectarian media, suffers from a paranoid "persecution complex" and exhibits a "sense of entitlement" vis a vis other Americans.

Christianity Today magazine thought Stewart's prior conspiracy theory "sometimes borders on the comical." But she typifies other liberal assessments of Jan. 6. Journalism should offer a balanced assessment of the extent and influence of those she brands as "theocratic extremists," naming in particular Ralph Reed's Faith and Freedom Coalition, Chad Connelly's Faith Wins, and the Texas-based United In Purpose.

Rabey's article cited above helpfully scans the variety of evangelical reactions to Jan. 6th. Outspoken pro-Trump preachers appear alongside conservative Protestants who decry the former President's rejection of the 2020 election results and believe his Christian followers are damaging the faith's credibility and prospects, for example David French of TheDispatch.com and the Rev. Russell Moore of Christianity Today.

These dissenters should be tapped alongside the clergy famed for Trump or Republican fealty.

Reporters might also want to hear from Jan. 6th committeeman Adam Kinzinger, a controversial anti-Trump Republican who is leaving Congress. Kinzinger was raised by a father who long led a ministry that provides shelter, food, and job training for the homeless in Bloomington, Illinois. He's a decorated Air Force combat veteran and counts among the serious-minded Christians on Capitol Hill (see here and here). Not long ago, that qualified him for evangelical favor and bright Republican Party prospects.

FIRST IMAGE: Screenshot drawn from various social media posts built on CNN coverage.