If you have followed GetReligion for a decade or so, you know that our religion-beat patriarch Richard Ostling writes a “Memo” post every week in which he focuses on religion trends and future events to which journalists should be paying attention.

This week’s Memo focused on why religious and secular debates about Death with Dignity laws will not be fading away anytime soon. As always, Ostling’s Memo posts are packed with links to relevant interest groups, experts and online resources to aid reporters.

This brings me to this week’s “Crossroads,” which — for a change — does not focus on a religion-news story in the mainstream press (click here to listen to the podcast). Instead, you can think of this feature as a kind of Mattingly Memo, in which host Todd Wilken and I discussed the news (and religious) implications of a new Atlantic Monthly essay by Jonathan Haidt that ran with this dramatic double-decker headline:

The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls

The preponderance of the evidence suggests that social media is causing real damage to adolescents

On its face, this essay was not a “religion news” piece at all. From my point of view, that was kind of the point.

One of the themes Haidt stressed was that teen-aged girls are pretty much alone, when it comes to wrestling with the moral, emotional and even medical side effects of addiction to social media — the invasive visual-image wonderland of Instagram, in particular. The article includes a depressing file of research slides on this mental-health issue from the Wall Street Journal (click here for that .pdf). Note, in particular, that teens believe their parents have next to zero understanding of what is going on.

If parents are tuned out, where does that put clergy? Should religious leaders be playing some kind of role in public-square (and personal) discussions of this issue?

These questions made me think of an “On Religion” column that I wrote in 2017 about the efforts of some Colorado teens — reacting to several suicides linked to cyber-bullying — to help their friends examine the impact of social-media programs on their lives. The result was “App-Free October,” a project that asked young people to un-plug several major social-media programs for one month, while substituting face-to-face activities (hiking, cooking, visiting the elderly) to help themselves and others. Their efforts caught the attention of the head of the Catholic Archdiocese of Denver.

Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila knew all about the suicides, of course, with 72 Colorado students taking their own lives in 2015 and another 68 in 2016. …

"One theme that I see running through the stories of teens who struggle with suicidal thoughts is the pervasive influence of social media on their identity and sense of self-worth," stressed Aquila, in his regular Denver Catholic column. "The teenage years have always been a time of uncertainty, as physiological and emotional development takes place."

It's controversial, of course, to link smartphones, social media and suicide. But the painful reality is that bullying is often linked to suicide, wrote the archbishop, and bullies now use social-media apps – along with the nearly 80 percent of ordinary teens whose daily lives include regular, or obsessive, use of Snapchat and Instagram.

Bullying always "attacks the basic dignity of another human being through demeaning the person," wrote the archbishop. With smartphones everywhere, "bullies gained access to their peers on a scale never seen before. Not only did fallen human nature obtain a virtual megaphone it could use 24/7, but the anonymity offered by some apps removed the accountability provided by platforms that require users to identify themselves.

This brings me back to Haidt and the essay in the Atlantic.

The key is that something went terribly wrong in the lives of young females about 15 years ago — about the time that the iPhone ushered in the age of smartphones. Here is his overture:

Social media gets blamed for many of America’s ills, including the polarization of our politics and the erosion of truth itself. But proving that harms have occurred to all of society is hard. Far easier to show is the damage to a specific class of people: adolescent girls, whose rates of depression, anxiety, and self-injury surged in the early 2010s, as social-media platforms proliferated and expanded. Much more than for boys, adolescence typically heightens girls’ self-consciousness about their changing body and amplifies insecurities about where they fit in their social network. Social media — particularly Instagram, which displaces other forms of interaction among teens, puts the size of their friend group on public display, and subjects their physical appearance to the hard metrics of likes and comment counts—takes the worst parts of middle school and glossy women’s magazines and intensifies them.

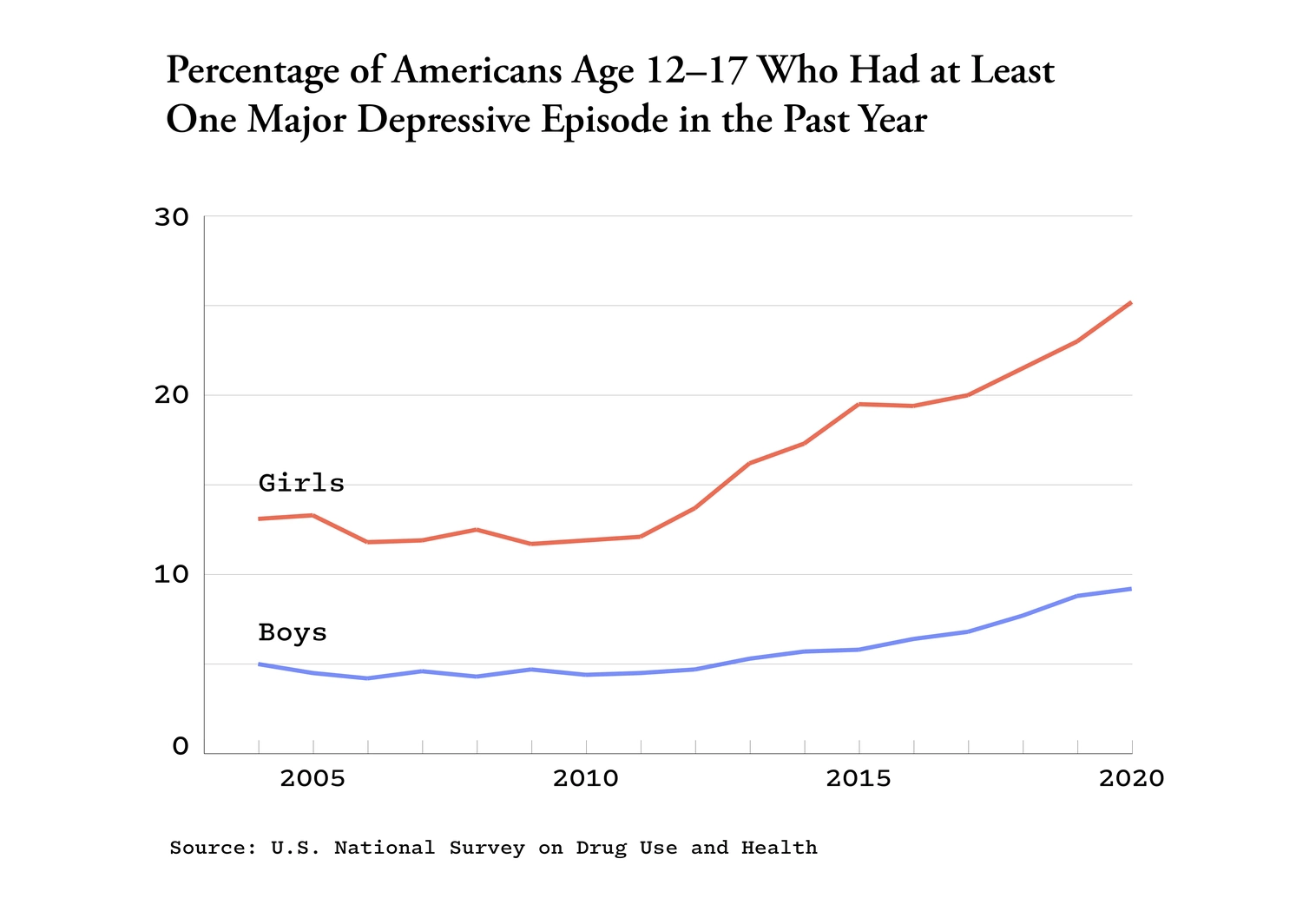

The article includes his chart, which shows one of those “elbow” jumps that are becoming more common in our high-tech lives.

To be blunt, argues Haidt:

Something terrible has happened to Gen Z, the generation born after 1996. Rates of teen depression and anxiety have gone up and down over time, but it is rare to find an “elbow” in these data sets — a substantial and sustained change occurring within just two or three years. Yet when we look at what happened to American teens in the early 2010s, we see many such turning points, usually sharper for girls.

The article includes all kinds of information about the debates linked to these changes, including the arguments of cyber-czars who point to other explanations of these rapid changes.

I kept thinking back to the early 1990s, when I taught mass-media courses at Denver Seminary, trying to help seminarians grasp the degree to which entertainment media, and to a lesser extent news, dominated the lives of the people in their pews and the unchurched (click here for an essay on that academic project, which ultimately failed).

I kept asking these questions, in an attempt to find a practical definition of “discipleship” — How do you spend your time? How do you spend your money? How do you make your decisions?

The issue, at that time, was cable television. But we knew the Internet was coming. We knew that the digital age would change lives forever.

This would affect parents and children. Think about it: If television sets were doors into homes, what are the omnipresent smartphones that young people (and their parents) consult dozens (some say hundreds) of times every day?

There are questions here for parents, pastors and reporters. Near the end of the Atlantic piece there is this:

Right now, families are trapped. I have heard many parents say that they don’t want their children on Instagram, but they allow them to lie about their age and open accounts because, well, that’s what everyone else has done. Dismantling such traps takes coordinated action, and the principals of local elementary and middle schools are well placed to initiate that coordination. …

If public officials do nothing, the current experiment will keep running — to Facebook’s benefit and teen girls’ detriment. The preponderance of the evidence is damning.

Enjoy the podcast?

Maybe. It’s sobering. However, please, pass this podcast along to others (especially clergy and reporters).

FIRST IMAGE: From the Offline October Facebook page.