The myth of the Catholic voter -- in France

A recurring feature in our repertoire at GetReligion is the critique of articles that posit the existence of a monolithic Catholic vote. Mindful of the need to educate reporters, TMatt has written a four-part aria harmonizing these eternal verities.

Here is the refrain from his "Four basic 'Catholic voter' camps":

* Ex-Catholics. While most ex-Catholics are solid for the Democrats, the large percentage that has left to join conservative Protestant churches (including some Latinos) may lean to GOP. (Tenor)

* Cultural Catholics who may go to church a few times a year. This may be an undecided voter — check out that classic Atlantic Monthly tribes of American religion piece — depending on what is happening with the economy, foreign policy, etc. Leans to Democrats. (Soprano)

* Sunday-morning American Catholics. This voter is a regular in the pew and may even play some leadership role in the parish. This is the Catholic voter that is really up for grabs, the true swing voter that the candidates are after. (Alto)

* “Sweats the details” Roman Catholic who goes to confession. Is active in the full sacramental life of the parish and almost always backs the Vatican, when it comes to matters of faith and practice. This is where the GOP has made its big gains in recent decades, but this is a very, very small slice of the American Catholic pie. (Base)

Can this song be played elsewhere? It is a fair description of the American political scene, but will it work in Europe? It is all but impossible to transpose American political norms to a European setting, but there are echoes to be heard in a recent spate of French articles.

Paris Match looks at the religion outreach efforts of the candidates in its 16 March 2012 issue. The weekly magazine states that while the French census does not record religious affiliation, an April 2011 survey conducted for Le Journal du Dimanche found that 61% of French people define themselves as Catholic, but only 15% of the population are regular mass-going Catholics.

"Religion continues to be strongly related to voting behavior,” said Jerome Fourquet, [director of the Institut français d'opinion publique]. Catholics traditionally vote right, and this orientation is stronger among active Catholics. Muslims back the left by 90%. Since the second Intifada (early 2000s), Jews are turning more to the right. Protestants, long close to the radical socialist party, are moving slowly to the right.

A small shift of Muslims to the right or Catholics to the left would have a significant impact in the election, "Les politiques tentent de convertir les croyants" argues. While Paris Match notes the correlation between regular attendance at mass and conservative voting patterns, it does not develop this theme. The article focuses on the attempts by the different political parties to broaden their appeal, or in the case of President Sarkozy, win back alienated voters.

The international news channel France 24 has an interesting story entitled "In secular France, can faith carry the election?" that presents an interview with a sociologist who argues that religion, more than class, determines voting patterns. It offers some interesting statistics.

At 57.2%, Catholics make up the majority of voters in France. Muslims (5%) form the second biggest religious group, followed by Protestants (2%) and Jews (0.6%). Some 30% of French voters describe themselves as having “no religion”.

...French Muslims are largely left-leaning – 95% of them voted for [Socialist candidate] Ségolène Royal in the first round of the 2007 presidential election, while only 5% voted for [conservative, UMP party] Nicolas Sarkozy. Around 75% of French Muslims are working class, but the French working class as a whole does not vote in the same way. In fact, they span left, right and far-right circles. Because of this comparison, we can deduce that French Muslims tend to vote left-wing because of their membership of a religious group rather than their social class.

... Practicing Catholics are five to six times more likely to vote right-wing than those who describe themselves as “without religion”. ... Interestingly, Catholics have not been won over by the far right. In 2007, [former National Front leader] Jean-Marie Le Pen experienced his lowest score among French Catholics.

... We do know however that French Jews are more likely to vote left than right. ... But it’s difficult to know why because their vote is clouded by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Historically, Protestants have tended to side with the left. But this tendency has weakened in recent years ...

The interview concludes with the question "Will religion play a part in the 2012 election?" It produces this answer:

The religious vote is grounded in values, which explains why it varies remarkably little. It is not new to France, the only difference now being that Islam has made it a focal issue.

There is more nuance in this story than the Paris Match article, as France 24 notes that subsections within the Catholic population display different voting patterns. The more active in their mass-going, the stronger their identification with the right (but not the far right.)

However, a 11 January 2012 article in Le Croix fleshes out the Catholic voter phenomena and gives a Continental version of TMatt's four noble truths. There is no such thing as a typical Catholic voter, the French Catholic daily writes. Catholics are active in across the political spectrum and are bringing their faith to their parties, not their parties to Catholic Church. "In France no political party has been capable of uniting the Catholic world."

Historian and sociologist Philippe Portier told Le Croix that a new "Christian identity is coming to the fore".

Historian and sociologist Philippe Portier told Le Croix that a new "Christian identity is coming to the fore".

"Under the influence of John Paul II’s pontificate, those Catholics who until then had kept a low profile, owing to social crises and their minority situation, decided to make themselves heard", is Portier’s analysis. Not necessarily by joining a Christian party but by reaffirming their positions and opting for greater visibility.

The article notes the formation of the "Poissons roses" movement which seeks to form a "Christian current" within the socialist parties. "We don’t have to describe ourselves as Christians to defend our vision of the family or those who are about to die", its leader Philippe de Rouxhe said. But "we have to be more visible within the public realm."

While Catholics are seeking to colonize the socialist parties, the Civitas movement, which is closely allied to the Society of St Pius X (SSPX), seeks to strengthen the traditional royalist Catholic right and

intends to make a place in the political arena to restore "the social kingship of Our Lord Jesus Christ."

Across party lines Le Croix finds openly Catholic politicians. Senator Anne-Marie Escoffier, a member of the left-wing Radical Party, told the newspaper she was "never criticized" on the left for her faith, while conservative MP Jacques Remiller, author of a recent petition denouncing "Christianophobia", describes himself as someone "who fully assumes his own faith."

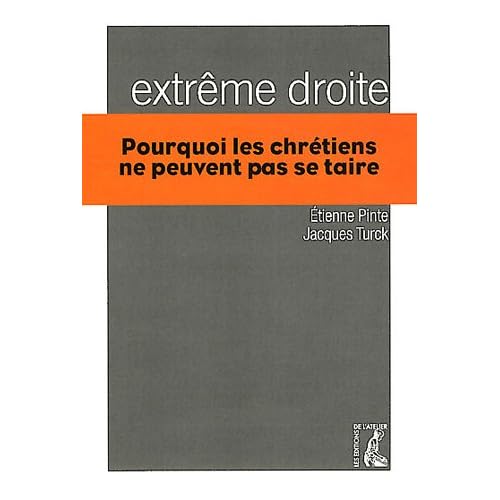

Only on the far right is there friction between the church and politics. La Stampa's Vatican Insider reports that a book published in January entitled Extrême-droite, pourquoi les Chrétiens ne peuvent pas se taire (The radical right: Why Christians cannot keep silent) by Etienne Pinte, a conservative MP, and Fr. Jacques Turck, former director of the French Episcopal Conference’s (CEF) National Council on the Family and Society, places an

emphasis on the incompatibility of the Gospel’s values and the Church’s social doctrine with the political plans of radical right parties. ... “Our book – said Pinte in an interview with French magazine Témoignage Chrétien (Christian Testimony) – does not tell people not to vote for the National Front party but reminds Christians that they would be contradicting themselves if they adopted its ideology.”

This view of the FN has subsequently been endorsed by Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, the Archbishop of Paris and President of the CEF.

As an aside, the unasked question in the French articles I find intriguing is the Muslim vote. Is this a religious, class or an immigrant phenomena?

What then can we say about the Catholic vote in France? Is it monolithic or break along active/non-active lines? Is there no such thing as a Catholic vote? Does it follow the same sort of general patterns in France as in the U.S.? Where I am going with all of this is in saying that religious identity, practice and belief (and even the lack there of) is so deeply ingrained within the person, and so variegated across society, that short hand statements like the "Catholic vote" will always be false (inadequate?) in describing life -- even in France.

What say you GetReligion readers? Should we retire the "Catholic voter" meme, or does it still have its journalistic uses?